Authors interview authors

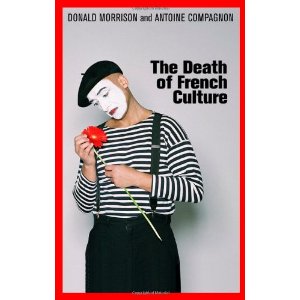

Within days of Time magazine's publication of Don Morrison's article on the decline of France as an international cultural power, French media "lit up like the Eiffel Tower in full sparkle". Major French figures like Didier Jacob, Maurice Druon, Teresa Cremisi, Olivier Poivre d'Arvor, and François Busnel, weighed in. The blogosphere went wild. Even foreigners got involved. US Ambassador Craig Stapleton wrote a letter--defending France. Feeling that 3000 words were insufficient to explore such a complex subject, Morrison has now written an expanded book: The Death of French Culture, with a response by Antoine Compagnon, Professor of Literature at the Collège de France. Questions by Laurel Zuckerman, of Paris Writers News.

LZ: Why do you think your original article caused such a strong reaction in France?

LZ: Why do you think your original article caused such a strong reaction in France?

DM : More than almost any other country, France takes culture seriously. For centuries, it has been an element of French diplomacy, national identity and the "gloire" that sets France apart from lesser nations. Only France proclaimed a "civilizing mission" to imbue colonial subjects with, among other gifts, France's cultural heritage. Even today culture remains one of France's unique selling propositions. As, a French diplomat once proclaimed, "Germany may have Siemens, but we have Voltaire." So anyone who makes critical remarks about French culture, no matter how accurate or well-meaning, should be prepared for a strong reaction.

LZ: How did you get interested in the question of French culture?

DM :I went to a small high school in a small mid-American town, where a small but very tough nun pounded a few words of French into my skull -- along with a lifelong fascination with the culture and history of this seemingly exotic country. I thought I'd never visit the place. But when I did, many years later, I was astonished to find that people pretty much understood the strange sounds I was able to summon from the mists of memory. One thing led to another, and I'm still here, still fascinated.

DM :I went to a small high school in a small mid-American town, where a small but very tough nun pounded a few words of French into my skull -- along with a lifelong fascination with the culture and history of this seemingly exotic country. I thought I'd never visit the place. But when I did, many years later, I was astonished to find that people pretty much understood the strange sounds I was able to summon from the mists of memory. One thing led to another, and I'm still here, still fascinated.

LZ: You point out how language, education, cultural bureaucracy contribute to the death of French culture. Let’s talk about language first.

Use of French is declining very quickly. Only 33 high Chinese high schools out of 15,000 offer French classes. In England French is no longer required and major US universities are dropping their French departments. Is this inevitable? What is to be done?

DM :This trend troubles me greatly, considering how hard I've tried -- and largely failed -- to master French. I used to applaud France's strenuous efforts to promote French as an international language, but I'm beginning to think it's not worth the trouble. A French president walking out of an international forum because one of his countrymen addresses the audience in English? French diplomats slowing down the work of multilateral organizations with demands that French be an official language? Quotas limiting other languages heard on French radio and TV? Millions of euros a year spent on La Francophonie and similar extension efforts? I wonder if those resources could be put to better use. They aren't going to halt the rise of English. That's a fact of globalization. It affects German, Italian, Gujarati and Cantonese just as it does French, but for some reason other countries don't twist themselves into pretzels trying to resist it. I wonder if France's resources would be better spent ensuring that its culture is more robust and exportable, rather than produced in French.

DM :This trend troubles me greatly, considering how hard I've tried -- and largely failed -- to master French. I used to applaud France's strenuous efforts to promote French as an international language, but I'm beginning to think it's not worth the trouble. A French president walking out of an international forum because one of his countrymen addresses the audience in English? French diplomats slowing down the work of multilateral organizations with demands that French be an official language? Quotas limiting other languages heard on French radio and TV? Millions of euros a year spent on La Francophonie and similar extension efforts? I wonder if those resources could be put to better use. They aren't going to halt the rise of English. That's a fact of globalization. It affects German, Italian, Gujarati and Cantonese just as it does French, but for some reason other countries don't twist themselves into pretzels trying to resist it. I wonder if France's resources would be better spent ensuring that its culture is more robust and exportable, rather than produced in French.

LZ: Should the French communicate in English in order to be heard? What options do they have?

DM : For good or ill, English is increasingly the language that other countries use to speak to each other. They still retain their national languages, as France surely will. Actually, despite its protestations, France is dealing with that reality fairly well. English is widely taught in schools from an early age. Many French multinational companies use English as a working language. French rock and pop musicians perform in English. French is never going to disappear. But even if it is less widely spoken than it was a decade or two ago, France is no less prosperous or secure as a result. On the contrary.

LZ: French education policies have devastated the study of French literature in France : destruction of the L bac option, ruin of literature and social sciences in French universities (“Three times more space for a Bresse chicken than a French university student.”) Why this neglect? Will the 5 billion euro "Plan Campus" improve things? Autonomy?

LZ: French education policies have devastated the study of French literature in France : destruction of the L bac option, ruin of literature and social sciences in French universities (“Three times more space for a Bresse chicken than a French university student.”) Why this neglect? Will the 5 billion euro "Plan Campus" improve things? Autonomy?

DM : The sad state of French universities has been a topic of national debate for years, and I'm pleased that the problem is being addressed. It's obvious that a country's future is linked to the quality of its education, and universities have long been a weak link in the French system. In particular, France could improve the vigor of its culture by turning its universities into centers of cultural excellence -- where literature and the arts are not just studied intensively as academic subjects but also as performing professions, with appropriate performing facilities. That would help develop not only the next generation of writers and artists, but also the next generation of cultural audiences. Other countries do this. France can too.

LZ: “Excessive cultural subsidies suffocate creativity” how? Who decides which artists get support in France?

DM : On a per-capita basis, France subsidizes culture more heavily than just about any other country. It's a well-meaning attempt, but it has the perverse effect of promoting safe, predictable works by cultural producers seeking subsidies. It doesn't help that the subsidies are doled out by cultural bureaucrats. True, they tend to be functionaries of impeccable taste and exacting standards, but they are bureaucrats nonetheless -- not audiences. This intensive subsidization also encourages the production of culture that appeals to a national audience, as distinct from an international one. Thus, French culture has a tendency to become "franco-francais" rather than internationally appealing. French artists and writers are encouraged to address a French audience, and not to produce works that succeed outside France. Similarly, subsidies and other protectionist measures tend to insulate France from foreign cultural influences, to the detriment of its culture. History has shown that exposure to and competition with foreign influences keeps a nation's culture vital. Of course, everything I've just said is a generality. In practice, French culture is alive and well, and some of it exports well. But that's despite subsidies, not thanks to them.

LZ: What is the role of favoritism and incompetence in the failure of official French cultural organizations to spread French culture?

DM :These practices are surprisingly rare among French cultural officials, who in my experience are mostly fair and scrupulous in their duties. But the bureaucratic structure in which they operate -- the system that gives them vast power over who gets rewarded, hired, promoted and subsidized -- is inherently open to abuse. It's an accident waiting to happen.

LZ: Is a Ministry of Culture harmful? Or is it the quality recent ministers (Jacques (‘loi’) Toubon, Chrisine Albanel (who so infuriated the brilliant Bartabas that he wrecked her office); Frédéric Mitterand (currently in hiding)? Could a great Culture Minister turn things around? How?

DM : Nearly every country has a culture ministry, but few have one as big and powerful as France's -- one that sucks all the air out of the cultural space in France, that makes all the big decisions about culture. The effect is that the French tend to view culture as a public utility, one they have no control over and feel little responsibility for. Actually, I think France has had some effective and truly visionary culture ministers, from Andre Malraux right down to Frederic Mitterrand -- who, by the way, is not in hiding. He's in the papers nearly every day, and I'm going to see him at a conference in a few weeks. But does any country need an all-powerful minister to determine the course of the nation's culture? Or would culture be better served by making its beneficiaries, i.e. you and me, more responsible for its progress, and more empowered to help decide its future?

LZ: Why do French writers make such a small splash outside France? Is this really a quality problem or one of industrial organization?

DM : You could argue that it's a quality problem, that French writers since the dawn of the nouveau roman have favored spare, elegant, bloodless fiction beloved of critics but shunned by readers, especially those abroad. But it's also a problem of competition: too many writers in other countries produce novels bursting with plot, character and color, which do indeed travel well. I'm not talking just about commercial novels, but also "literary" fiction. You see these writers, mostly foreigners, all over the best-seller lists, even in France. There's also a problem of publishing economics. Translations cost money, and foreign publishers are facing hard times in many countries. It's easier for them to feast on the abundance of local writers. But mostly I think it's the fact that too many French novelists are not focusing on the real state of contemporary France, its fascinating national debates and its very serious problems. In my admittedly biased view, contemporary French fiction can be thoughtful, introspective and formally inventive -- but not especially connected to contemporary France.

LZ: You've said that French writers tend not to engage with current events. What is the role of taboos in stifling French writers? (A few years ago, telling the truth about Algeria was still a punishable offense; French students study the Vietnam War more than the colonial war in French Indochina; and the American slave trade more the history of slavery in French colonies).

DM : I'm not sure taboo is the right word. It's more a matter of timing and priorities. It took American novelists two decades to address the Vietnam war in a serious and concerted way. Somehow, the subject was considered too sensitive, too unresolved or otherwise not ripe enough for thoughtful engagement. France's behavior during World War II is finally getting its due, and I'm sure other sensitive historical subjects will follow. We are, for instance, beginning to see some good writing about the immigrant experience in France. As the country's dispossessed minorities find their voice, we'll see more good, topical fiction.

LZ: How to write the Great French Novel ? Should an outsider write it? An expat, for example?

DM : I don't think you'd have to be an outsider to capture the essence of France, Frenchness and all the other things that might constitute a great national novel. After all, being a writer means being able, or at least willing, to look at the world through different eyes, to apply imagination to reality. That said, it's interesting that so much great American and British fiction has come from first- and second-generation immigrants, including the great postwar Jewish-American writers, and the impressive younger writers with roots in Britain's former colonies. I expect to see a similar wave of excellence coming from the margins of French society.

LZ: Many of the great internationally known icons of French culture were (or are) Jewish. (Proust, Perec, Marcel Marceau, Goscinny, Levy Strauss, Derrida, Aron, Bergson, Durkheim, Cyrulnik, Gainsbourg, Barbara, JJGoldman, Berger, Truffaut, Simone Signoret, Reza, Finklekraut, Glucksman, BHL) Has French culture been permanently impoverished by its treatment of Jews in WWII?

DM : The entire world has been impoverished by the Jewish tragedy of World War II. France is not alone. And coming to terms with the war is a task for France, not for me. But I do live in France at a time when, for rather shabby political reasons, other French minorities are being marginalized, told what not to wear and where not to live and, in one shocking case, singled out for deportation. I wonder if, someday soon, we might start asking ourselves how many potential French cultural geniuses were lost or thwarted by such policies.

LZ: Let’s talk money. For a foreigner the treatment of billionaire François Pinault, who wanted to turn Ile Séguin into a great art museum but got so frustrated by French politicians and bureaucrats that he moved the project to Italy, is absolutely inexplicable. What happened here? Is this why French billionaires give so little to culture?

DM : You'd have to ask M. Pinault what went wrong, but I suspect he grew tired of dealing with a glacial bureaucracy. He is not alone. You'll recall that Helmut Newton decided not to give his photographic collection to France after a similar experience. The overweening power of France's cultural mandarins may have something to do with this. In addition, France is still in the process of developing a habit of cultural philanthropy. Recent tax reforms should help encourage donations. But the mere existence of a giant bureaucracy subsidizing and controlling French culture tends to make the French feel that supporting culture is not their individual responsibility.

LZ: What is culture? How is it spread? What makes it powerful? Could we imagine the Chinese taking cultural leadership?

DM : To quote the great Duke Ellington, when asked where jazz was headed: If I knew the future of culture, I'd be there. There are many definitions of culture, but if you're talking about serious works of literature and the plastic arts, then its global influence can be measured, imprecisely, by such things as reputational surveys and auction results. This isn't the same as quality or vitality, which remains largely subjective. By the first set of measures, France is not doing so well these days. But I think books like mine are starting to ignite a national debate on re-invigorating French culture and making it more successful abroad. As for China, I recently returned from two years of teaching there. The country has a long and distinguished cultural tradition, and the contemporary art and literary scenes are exciting. But culture thrives in a climate of openness, and China is just beginning to confront this fact. The next few years will be interesting.

LZ: Should an English-speaking writer publish in France? (given how hard it is to sell foreign rights from France).

DM : A number of English-speaking writers do quite well in France: Douglas Kennedy, Nancy Huston, Diane Johnson, Stephen Clarke, Paul Auster. Many French publishers provide the kind of attention and support that their Ango-Saxon counterparts no longer do. That was certainly my experience, with Editions Denoel. And France is a warm and welcoming place for foreign writers. Even annoying ones like me. In China, I would ask my students to imagine that a foreign writer came there and wrote a book about "the death of Chinese culture." What would happen to him? I asked. Would he be fired from his teaching job? (Heads would nod around the room.) Arrested? (More heads nod.) Deported? (Everybody nods.) Well, I tell them. I am that man. And here is what happened to me in France. My arguments were reported faithfully in the major media. I was a frequent guest on French TV. France's top cultural officials invited me to have lunch, speak at their conferences and write for their in-house publications. And a pillar of the French publishing establishment gave me a book contract. So that's how you deal with your critics. And that's why I think France will always be a great place for the people who make culture, no matter where they're from.

The Death of French Culture, by Donald Morrison and Antoine Compagnon, Polity Press

Donald Morrison is former editor of Time magazine's European and Asian editions

Laurel Zuckerman is the author of Sorbonne Confidential and the editor of Paris Writers News.

WRITERS: ONLY TEN MORE DAYS TO SUBMIT TO THE PARIS SHORT STORY CONTEST!

http://parisstoriescontest.blogspot.com/

Banned Book Week celebrates the "Freedom to Read" from Sept 21 to Sept 27.